The Hidden Details in Charles and Camilla’s Coronation Portraits

the King and Queen's new portraits contain centuries of royal tradition...but also quietly paint over the script

👑 Correction Note (May 15, 2025): In the original version of this post, I misstated a few key details about Queen Camilla’s coronation attire. She did not wear the George IV State Diadem at the coronation—that look came from the State Opening of Parliament, where she re-wore her coronation gown. Also, the Coronation Necklace was worn at the coronation, pendant included.

Many thanks to a thoughtful friend of the page who flagged the errors! This was an unforced error on my part. Onward with better fact-checking and continued appreciation for this eagle-eyed community.

It’s a royal tradition more than 400 years in the making: the unveiling of two official portraits meant to capture the essence of a monarch. Last week, on May 7, 2025—two years after their coronation—the first painted portraits of King Charles III and Queen Camilla were revealed to the public.

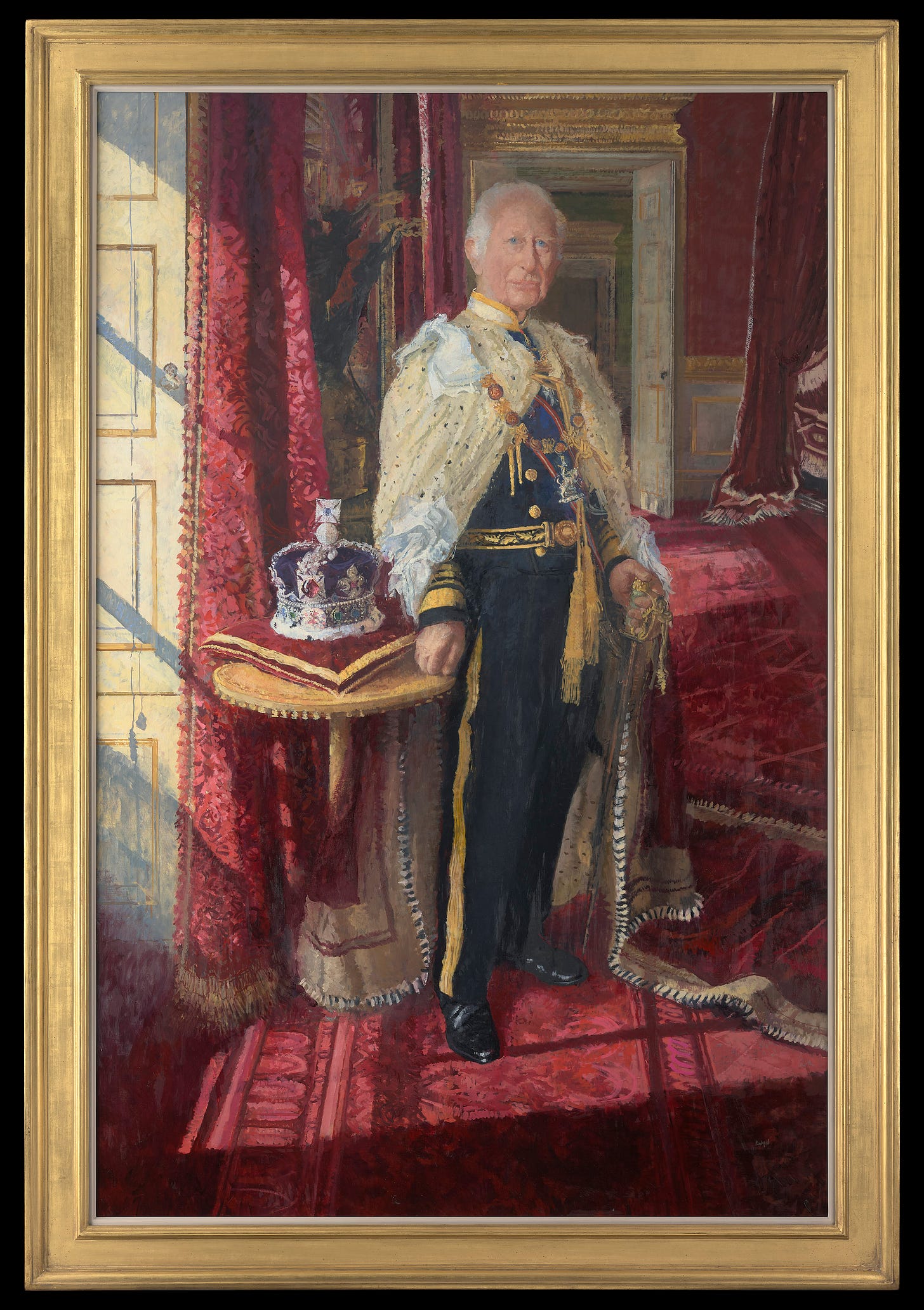

Each chose a different artist to capture their likeness. King Charles selected Peter Kuhfeld, a painter with deep royal ties. As

of Write Royalty points out, Kuhfeld was fresh out of the Royal Academy Schools when Charles first commissioned him to paint a portrait of young Princes William and Harry—then just 5½ and 3½ years old. He has remained a favored artist ever since, painting Charles multiple times over the years.For more context, I highly recommend Treble’s recent newsletters on Charles’ reign as the so-called “Arts King,” which explore not just these new portraits, but also his broader patronage. From commissioning artists to document his coronation to championing a year’s worth of arts-focused public engagements, it’s nice to once again have a monarch who cares about the arts.

Charles has known Kuhfield for more than 40 years, and the painter has also accompanied the King on many of his foreign tours as the official Tour Artist (something I find to be a truly delightful royal practice!). His style is loose and painterly—lending a vibrant, impressionistic quality to his subjects.

I find Kuhfeld’s dynamic approach to be the perfect lens for applying some pep to Charles’ step; after all, this is a man who waited in the wings for seven decades before receiving his crown. Why not play up his more spirited side with a little bit of paint?

With the weight of monarchy finally settled on his shoulders, Kuhfeld’s latest portrait doesn’t just depict Charles—it celebrates his arrival. It’s a striking image, bold in both color and symbolism, standing in contrast to the more restrained style chosen by Queen Camilla, whose likeness was captured by contemporary portraitist Paul S. Benney.

Both paintings offer clues to how the new monarchs wish to be seen. So let’s take a closer look at each, starting with the King.

A King in the Spotlight

In Peter Kuhfeld’s portrait, King Charles III stands tall in the Throne Room at St. James’s Palace, sunlight streaming through a nearby window to spotlight the Imperial State Crown, which rests on a plinth at his side. It’s a traditional composition, steeped in the grandeur of monarchy—but Kuhfeld’s painterly style breathes fresh life into it.

The portrait took “over a year and a half” to complete, following five formal sittings with the King at both Windsor Castle and St. James’s Palace. Kuhfeld even conducted two additional sessions with the crown alone—an echo, perhaps, of the seriousness with which royal symbolism is treated in this very formal genre.

I’m particularly tickled by the note on the Royal Family’s website, which points out that the crown’s inclusion “follows established convention.” That callout feels like a bit of preemptive PR spin, doesn’t it? Perhaps a nod to the online discourse around colonial-era jewels and their contested legacy?

Still, Kuhfeld’s goal, as he explained in a statement, was to paint a monarch who feels “both human and regal”—a tricky balance to strike. There’s something to be said for the decision to place Charles quite literally in the sunlight, with the tools of monarchy close at hand…but not worn, suggesting a sovereign who is conscious of legacy without being consumed by it.

The Queen Consort, Up Close

Queen Camilla, by contrast, turned to contemporary portraitist Paul S. Benney—a self-taught artist known for his moody realism. The result is a photorealistic portrayal of the Queen Consort in her white silk coronation gown by Bruce Oldfield, her gaze steady and serene. The Queen’s crown rests nearby on an ornate gilded table, joined by her velvet Robe of Estate, rendered in exquisite detail.

The backdrop is a simple wash of deep teal, a modern choice that sets off the shimmer of the robe’s goldwork embroidery and the platinum tones of Camilla’s signature hairstyle. It’s more stylistically restrained than her husband’s portrait, but no less regal. Both her and Charles’ portraits share a similar pose: they each look directly at the viewer, projecting quiet confidence and self-possession.

Benney described his aim as striking a balance between “the grand and historic nature of the coronation iconography…and the humanity and empathy of such an extraordinary person taking on an extraordinary role.” He had six formal sittings with the Queen in the Garden Room at Clarence House, and was also granted access to set up a temporary artist’s studio there.

Benney also got up-close and personal access to Queen Camilla’s Coronation crown, writing on his website that he was able to “sketch and scrutinise” the “extraordinary object” for one day only. The piece had to be released from the Tower of London (with a security detail in attendance!) to his temporary studio at Clarence House. No pressure.

“If I never do another thing in my life,” Benney also wrote, “I will at least know that this work, as the only official Coronation State Portrait of Queen Camilla that will ever exist, will be part of our nation’s history. I am honoured and humbled by the King and Queen’s belief in my ability to do justice to this once in a lifetime commission.”

But by his own account to the press, the painting process was as personal as it was professional. “The sittings were extremely pleasurable on my part,” he told the BBC. “I like to talk when I'm painting… and so we had a lot of chat and stories which we told each other. At times I would be holding my tummy from laughing so much. The Queen is very witty.”

As for their reactions to the finished works? King Charles called his portrait a “wonderful composition;” Camilla put it more simply with, “I just love it.” Of course, they weren’t going to say anything else in front of the artists, cameras, and reporters—but their enthusiasm upon seeing the final images did seem genuinely warm.

Zoom in: Royal Accessories

In her portrait, Queen Camilla clasps a folded fan in her left hand—a detail that left royal fashion historian Rosie Harte intrigued.

After leaving a comment inquiring into this detail (which is not a convention of royal portraits featuring British Queens Consort) on Instagram, Harte received a reply from artist Paul S. Benney. “I had been…commissioned by the Worshipful Company of Fanmakers to design the Coronation Fan,” he wrote back. “It seemed [a] good idea to include it in the painting especially as the Queen has a large collection of fans of her own.”

This inclusion is more than a mere accessory; it symbolizes Camilla's personal connection to the art of fan-making. In February 2024, she was elevated to an Honorary Liveryman of the Worshipful Company of Fan Makers during a ceremony at Clarence House.

As for Camilla’s collection or the “official Coronation Fan,” I couldn’t turn anything up in some initial web searches, as typing “coronation fan” into Google mainly results in news articles beginning with phrases like “Royal Fans All Say the Same Thing As…” I’ll let you know if I have more luck in the future!

Regardless, the fan Camilla holds in the portrait not only highlights her appreciation for traditional craftsmanship but also intertwines her personal interests with her royal duties. It adds a layer of intimacy to the otherwise formal portrait.

Thanks, Rosie, for allowing me to include this fan-tastic detail in this newsletter!

Zoom in: Royal Robes

In his portrait, King Charles wears not the coronation regalia that sparked so many memes (“Party City costume,” anyone?), but instead the Royal Navy’s Number 1 Ceremonial Day Dress—complete with medals and decorations. It’s a dignified, restrained choice, and one with historical precedent.

While Queen Elizabeth II chose to be painted in her coronation gown for her official portrait, the Royal Collection Trust notes that male monarchs haven’t always followed suit. Both Edward VII and George V were depicted in military dress, as Charles now is.

That’s not to say the robes are absent. Draped over Charles’s shoulders is the crimson Robe of State—the same one he wore when entering Westminster Abbey to be crowned. Also known as the Parliament Robe, it features a long train of rich velvet trimmed with gold lace and ermine. It anchors the portrait in tradition without overwhelming it.

What the portrait doesn’t show is that there were actually four distinct robes worn by the King during the coronation. After the Robe of State, Charles donned the golden, Byzantine-inspired Imperial Mantle for the investiture. Then came the elaborately embroidered Robe Royal, worn at the exact moment of crowning. Finally, he departed the Abbey in the Imperial Robe—his great-grandfather King George VI’s from 1937, carefully restored by Ede & Ravenscroft for the occasion. Unlike Queen Elizabeth II, who commissioned a brand-new version in purple velvet, Charles opted for a piece of royal continuity.

His choice to be painted in the red Robe of State, rather than the more ostentatious Robe Royal or Imperial Robe, suggests a desire to highlight that continuity and constitutional duty over mere spectacle—perhaps a subtle nod to Charles’ own belief that he’s a working monarch rather than a gilded figurehead.

Camilla’s portrait includes her own symbolic textile: the Robe of Estate, seen beside her as she stands composed in her coronation gown. Worn as she exited Westminster Abbey, the robe was crafted from deep purple velvet by Ede & Ravenscroft and exquisitely hand-embroidered by the Royal School of Needlework.

Its golden design includes insects and 24 different plant species—a nod to the environment, and to Camilla’s personal connection to the RSN, where she has served as “dedicated” patron since 2017.

Among the motifs? Scabiosa, known as “pincushion flowers,” in a fitting tribute to her support of traditional needlework.

Zoom in: Royal Jewels

These new portraits also nod to the storied jewelry worn during the 2023 coronation—pieces steeped in centuries of tradition and political meaning.

During the ceremony itself, King Charles was crowned with the solid-gold St. Edward’s Crown (after receiving the Sovereign’s Sceptre and Orb, traditional emblems of monarchical authority).

Before leaving Westminster Abbey, however, he swapped it for the better-known Imperial State Crown—set with 2,868 diamonds, including the controversial Cullinan II. This crown, also used for the State Opening of Parliament, remains one of the most potent and visible symbols of the modern monarchy.

In Kuhfeld’s portrait, it sits gleaming beside the King, dramatically illuminated by sunlight. It could be a nod to the old adage, “The Sun never sets on the British Empire.”

Camilla’s ensemble in Benney’s portrait is equally rich in symbolism. Her white silk coronation gown is shown paired with the 22-carat Coronation Necklace, originally crafted for Queen Victoria in 1858 and worn by every crowned queen since. The first to wear it at a coronation was Queen Alexandra in 1902, followed by Queen Mary, Queen Elizabeth (the Queen Mother), and of course, Queen Elizabeth II in 1953.

Interestingly, Camilla chose to exclude one of the monarchy’s other most iconic jeweled pieces which was at her crowning in 2023: the George IV State Diadem. Created for King George IV’s 1820 coronation (and reportedly worn, on that occasion, over a velvet ‘Spanish-style’ hat), the Diadem is set with 1,333 diamonds, including a four-carat pale yellow brilliant. It has gone down in history as a symbol associated with female monarchy, and has featured promintently in official portraits of past Queens Consort.

Queen Mary, for example, posed wearing the Diadem while gesturing toward her more elaborate coronation crown in her 1911 portrait by William Llewellyn.

Camilla’s decision to keep her jewelry choices pared back in the painting—despite the historic gems at her disposal—adds to the realism of Benney’s portrait. It suggests a monarch more interested in continuity than spectacle, even when surrounded by centuries of inherited opulence. And Camilla seems to know that the only cranial adornment we really need in order to identify her…is her trademark blond feathered bob.

A Tradition in Painted Detail

Of course, this isn’t King Charles’s first brush with official portraiture. His earlier painted portrait by Jonathan Yeo—released in 2024, on the first anniversary of his coronation—was met with mixed reactions. Awash in a sea of crimson, the painting was widely compared to fire or blood, and was later defaced by animal rights activists protesting the monarchy’s ties to animal cruelty.

The protest and the outcry over how Charles was depicted underscores the modern pressures placed on royal portraiture: they need to symbolize not just authority, but also relevance, restraint, and core values.

A coronation portrait carries a different kind of weight from any other. These “grand, full-length” paintings have long served as the definitive image of a new sovereign—formal, commanding, and rich in symbolism. In earlier reigns, copies were distributed to courtiers, embassies, and allies as a visual assertion of the expectation of loyalty.

Charles and Camilla’s portraits now take their place in that centuries-old lineage. They are currently on display at the National Gallery in London for the public to view until June 5th, after which time they will move to their permanent home at Buckingham Palace. You’ll be able to see them there if you have summer tickets to tour the State Rooms.

These works are now part of the Royal Collection, whose holdings include the earliest known official coronation portrait: a stately image of King James VI and I, painted around 1620.

Four hundred years later, the tradition continues—modernized, personalized…but still unmistakably monarchical.

What do you think of the King and Queen’s portraits? Regal, restrained, or a little TOO real? There’s plenty to dissect—so tell me: which detail surprised you most? Let’s chat in the comments!

When you see both paintings side by side, Camilla's just feels colder. More detached.

It was shocking how “photoshopped “ Camilla’s looked. Was I the only one who thought this? The visibly slimmer and younger face and frame was shocking to me.