When Democracy Wears a Crown

we live in a world where democracy is starting to resemble an autocracy...and where royal institutions masquerade as meritocratic ones.

This past Saturday, two very different parades played out on opposite sides of the Atlantic.

In London, the British royal family marked King Charles III's official birthday with the traditional pomp and pageantry of Trooping the Colour. The sun was shining, the skies were clear…it was a rare but welcome burst of brightness.

The spectacle of soldiers, flags, music, and perfectly timed formations are always a visual affirmation of the monarchy as timeless and stately. And after the uncertainty of the past 18 months, it was a sorely needed display of the Royal Family’s ubiquity.

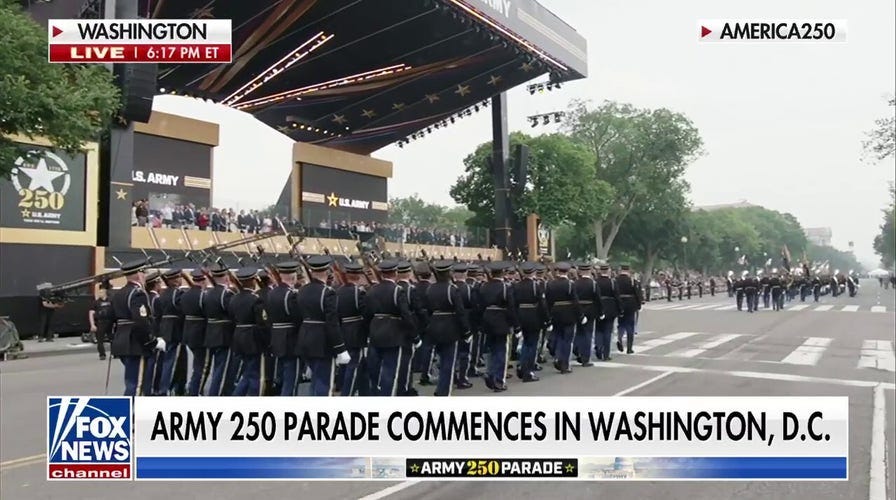

A few hours later, across the ocean, much of the U.S. East Coast remained under a dull, persistent gray. This summer has been more drizzle than dazzle so far—a fitting atmosphere for a democracy in turmoil. In Washington, D.C., a procession of military bands, tanks, and partisan rhetoric marched under the banner of #America250, a trial run for the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence next year.

Though intended as a bipartisan celebration of American heritage, critics quickly branded it “Trump's birthday parade” as this show of militarism and nostalgia centered suspiciously around one man.

Two parades. Two nations. And a strange reversal: the monarchy, historically a symbol of inherited power, is cloaking itself more and more in the language of “public service” and “impact.” Meanwhile, the actual republic—founded firmly on anti-monarchist ideals—is allowing itself to flirt with autocracy. This cultural and political swap is more than just symbolic. It reflects a deeper confusion in the 21st century about what power should look like, how legitimacy is performed, and who precisely is meant to serve their nation.

A Crown and Its People

The British monarchy has, in recent years, become increasingly adept at speaking the language of democracy. Words like “service,” “modernization,” and “impact” are now central to royal branding.

Much of this shift can be traced to the legacy of Queen Elizabeth II. Crowned in an age when monarchy was still regarded with suspicion in post-war Britain, she carefully curated an image of quiet dedication. Her 21st birthday vow that her “whole life, whether it be long or short, shall be devoted to your service,” became the cornerstone of her reign.

After her death, tributes often praised Elizabeth for “rising to the occasion” or “choosing service” (as if there had ever been a real choice in the matter). She came to embody duty over dominance and presented the Crown not as an instrument of power…but of steadfast national continuity.

Her successors have followed suit; King Charles III frames his reign as one of continuity and climate concern. Prince William portrays himself as a hands-on parent, mental health advocate, and relatable figure. The family is careful to suggest that their roles are not about privilege, but public service.

Of course, the royals are not elected. They cannot be removed from their roles by a nationwide swing to the opposite side of the aisle. Their lives are publicly funded, their roles inherited. Modernized language and trappings don’t negate the fact that the institution’s foundation remains firmly feudal. A constitutional monarchy can have a place in a modern world…but only if it is honest about what it is, and about the limited influence its members can (or should) have on a nation’s government, identity, and future. Pretending otherwise only invites confusion—and excuses power without accountability.

No Kings, but Many Coronations

Across the ocean, American politics is undergoing a stylistic transformation of its own—one that should unsettle anyone invested in democracy. The United States was founded on a rejection of monarchy. “No kings,” the protest slogan adopted by anti-Trump protesters this weekend, is not just a newfangled rallying cry…but a guiding principle. From our nation's first steps, leaders were to be accountable to the people. Power was to be checked and balanced.

And yet, in recent years, we have seen a rise in dynastic politics, personality cults, and authoritarian aesthetics. Public trust in institutions has eroded, while trust in individual strongmen has grown. And while Saturday's #America250 parade was ostensibly about the country, much of the coverage focused on the fact that it coincided with Donald Trump’s birthday.

Its style, tone, and language bore a striking resemblance to nationalistic displays usually seen in less democratic societies.

The paradox is stark: the country founded to abolish kings now toys with autocracy. The country defined by monarchy now performs democracy’s virtues for the cameras. This is a real problem.

When a monarchy wears the clothes of democracy, it becomes harder to critique. When autocracy adopts the symbols of patriotism and populism, it becomes harder to recognize. This mutual masquerade blurs our political instincts. Citizens will stop questioning inherited privilege if it’s swathed in charity work. They likewise stop noticing authoritarianism if it’s wrapped in American flags.

It is no coincidence that Trump’s far-right movement increasingly valorizes monarchy (or, at least, attempts its outward aesthetics). Think of the white gloves, the nostalgia, the clear hierarchy, the installment of sons in prominent positions. Think of the conservative influencers who promote femininity as "regal," or the political commentators who bemoan the loss of dignity and decorum and lineage in leadership. Royal aesthetics are no longer dismissed in American politics; they are emulated.

But these political players are not nostalgic for actual kings; they’re nostalgic for the myth of control.

Meanwhile, the British monarchy actually benefits from this cultural swap. So long as the Royal Family appears more democratic than the actual democracies, their existence will feel less outrageous. There’s less urgency to republican movements (despite their omnipresence at grand displays of monarchy, as we saw on Saturday).

From Getty, the Republic movement “advocates the replacement of the UK's monarch with a non-political head of state elected to a ceremonial or constitutional position to represent the nation, to defend democracy, to act as a referee in the political process and to offer a non-political voice at times of crisis and celebration.”

It’s worth noting the eerie symmetry in protest signage on both sides of the Atlantic. In the U.S., “No Kings” has reemerged as a rallying cry at pro-democracy demonstrations in a callback to our founding ideal that power should never be absolute or unaccountable.

Meanwhile, in the UK, signs reading “Not My King” have been held aloft by British republicans protesting the accession of Charles III—and challenging the idea that birth alone bestows legitimacy. Both underscore a growing unease with systems that place symbolism above the consent of the people.

None of this is to say that pageantry is inherently dangerous or that a nation’s ennobled first family must be thrown out wholesale. But when tradition is used to mask inequity, and when democracy becomes indistinguishable from dynasty, we should take a second to reevaluate.

For all their noble (pun inteded) intentions, the British royal family will never have “earned” their status. And American leaders should never be above the will of the people. If we forget those truths and allow ourselves to be comforted by empty imagery, we risk allowing both systems to drift further from accountability.

The unease we feel watching a Trumpian parade mimic a Coronation procession (or, for that matter, hearing royals speak like they’ve been elected to civil service) is not paranoia. It’s simply good judgment of the systems in which we live. We must keep the line clear.

Democracy may not be consistently elegant or dignified. But it is always meant to be ours.

Well said!