From oil paints to Instagram posts, royal image-making involves so much more than just putting faces on a canvas. Far from being mere decorative objects, royal portraits are propaganda. They project not only the individual sovereign…but also the very institution they embody. And they’re, of course, always erring on the side of flattery.

Every official royal portrait is a PR move, carefully composed to reflect how monarchs wish to be seen—and how the public expects them to behave.

But first…

Oops! A minor correction. In the original version of Tuesday’s newsletter (and the accompanying TikTok), I made a few errors regarding Queen Camilla’s coronation regalia.

While she did wear the Coronation Necklace (with the pendant) at the coronation, she did not wear the George IV State Diadem—that look came from her appearance at the State Opening of Parliament, where she re-wore her coronation gown. (Thanks a lot, Google Images). In the video, I also incorrectly stated that she wore the Queen Mother’s crown; in fact, Camilla wore a modified version of Queen Mary’s crown.

Thanks to a sharp-eyed friend of the page for pointing this out—and apologies for the mix-up. I've updated the posts to reflect the correct details!

And now, on to today’s topic…

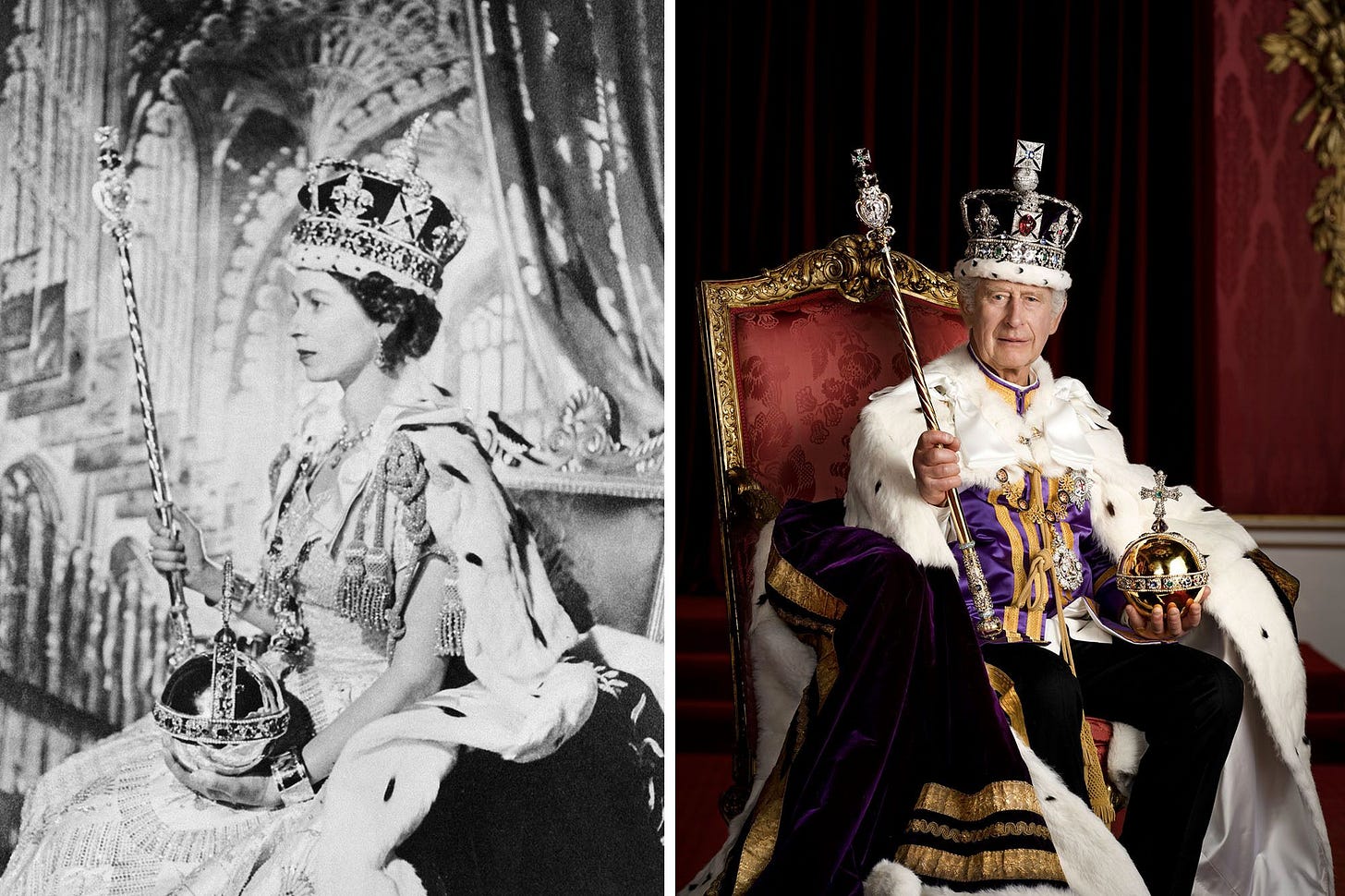

When approaching a royal portrait, it’s helpful to consider: “What does this image tell us about what the monarchy needed to project at that time?” It’s perhaps easier to pick up on those clues when we consider portraits from history, as textbooks and timelines neatly delineate cultural moments for us. But we can even apply this lens to modern portraiture.

We don’t look at images of King Charles or Queen Elizabeth II to answer “What does the monarch look like?” but rather: “What does the monarchy want us to believe about its figurehead?”

To better understand how royal portraits shape public perception, we can look to history—where time and distance make the messaging easier to decode. Let’s begin with a king who turned image-making into a weapon: Henry VIII.